What is Corneal Blindness?

Corneal disease is the second leading cause of blindness. Worldwide, there are an estimated 4.9 million bilaterally corneal blind persons who could potentially have their sight restored through corneal transplantation. Aside from disease of the cornea, trauma is another common cause of corneal blindness. U.S. eye banks provide nearly 70,000 corneas for transplant each year. For people suffering from corneal blindness, the only cure is a cornea transplant. Cornea transplants have a 98% success rate.

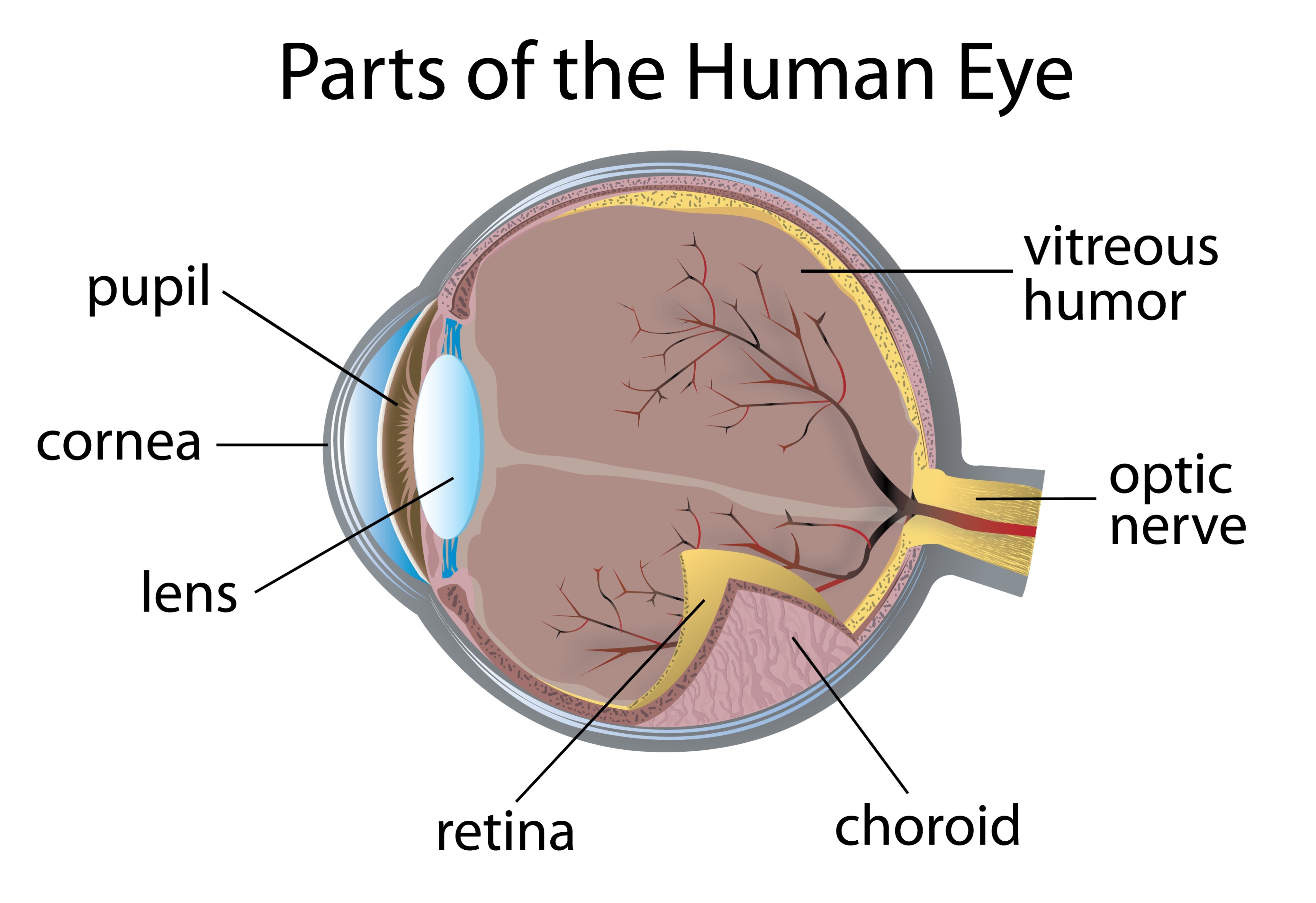

Corneal Anatomy

The cornea is the clear, front part of the eye where a contact lens would sit. The cornea is responsible for two-thirds of the focusing power of the eye. Because there is no direct blood supply to the cornea, there are very few disease processes in a donor that would rule out cornea donation. The cornea has 5 layers, but two of the most important are the epithelium and the endothelium.

The Epithelium

The epithelium forms the protective, outer covering of the cornea. Think of it like your skin, protecting you from the elements. Like your skin cells, corneal epithelial cells are continually sloughed away and replaced. The most significant danger to a donated cornea is the time between death and preservation. The eye ceases to produce tears after death. It does not take long for the epithelium to dry out, slough away, and expose the inner layers to infection.

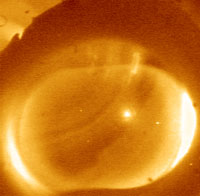

Slit-lamp micrograph of a healthy, donated cornea. Notice how it is translucent and smooth.

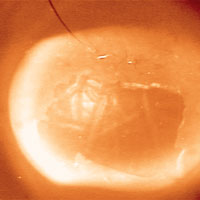

Slit-lamp micrograph of a cornea that has had a long death-to-preservation time. Note how a large area of the epithelium in the lower half has completely sloughed away. The folds you see are evidence of swelling. Finally, the white haze in the lower right corner is from the infiltration of white blood cells. This cornea cannot be transplanted.

The Endothelium

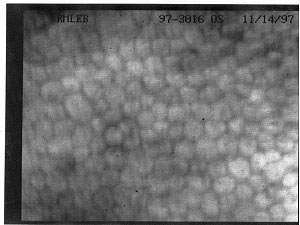

The endothelium is a single-cell layer on the back of the cornea. These cells' sole function is to pump water out of the cornea, thereby keeping it clear. When these cells fail, water builds up in the cornea, causing it to become opaque. These cells are critical to a successful transplant because they do not regenerate. What you are born with is what you get. While the average number of endothelium cells is around 5,000/mm2 at birth, you lose about 10% by puberty. As cells age and die, the others expand to fill the gaps. A cornea must have at least 2,000 cells/mm2 to be transplanted. Higher cell counts will typically be matched with younger recipients.

These endothelial cells remain viable for several hours after death. Recovery delays beyond 18 hours may render the cornea non-transplantable.

Specular micrograph of an endothelial layer of a donor cornea. These living cells are critical to a successful transplant, as they do not regenerate and must last the recipient's lifetime. Extended death-to-preservation times can put the endothelium in danger.